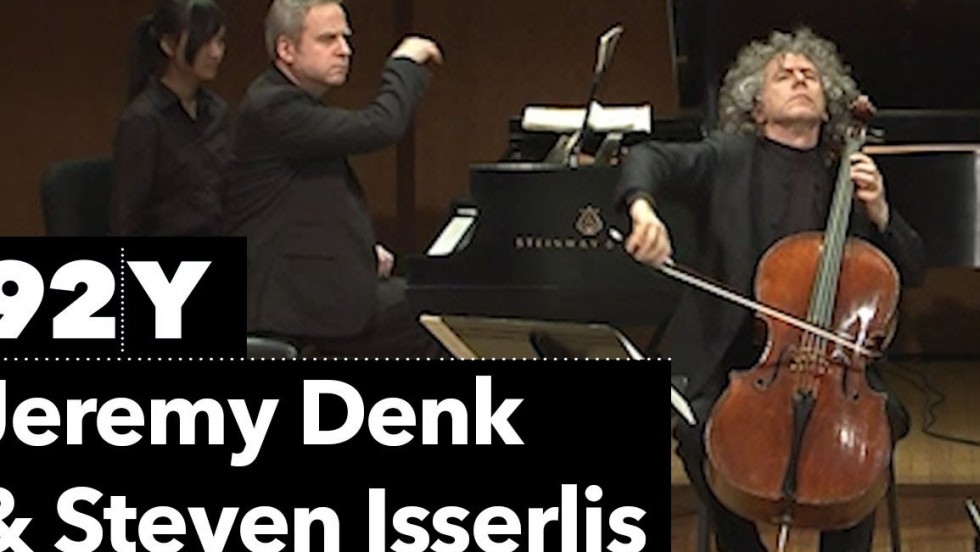

Joshua Bell, violin; Steven Isserlis, cello; Jeremy Denk, piano

Cookie Notice

This site uses cookies to measure our traffic and improve your experience. By clicking "OK" you consent to our use of cookies.

Virtuosos, stars, standouts: of course the members of this trio excel as performers. But the three longtime friends and collaborators are also compelling communicators and ambassadors who have variously defined what it means to be a

Program

Felix Mendelssohn Trio No. 2 in C minor, Opus 66

Dmitri Shostakovich Trio No. 2 in E minor

Sergei Rachmaninoff Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor

Maurice Ravel Trio in A minor

(Click on the composer to read program notes.)

Runtime: Approximately 1 hour and 54 minutes with intermission.

Prices, seating sections, and programs are subject to change.

Artist Videos

Artist Websites

Notes on the program

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy (1809-1847)

Trio No. 2, in C minor, Opus 66

Mendelssohn’s first published trio, the one in D minor (there was a juvenile work written much earlier), was enormously successful by virtue of its rich lyricism. The C-minor trio was composed six years later, during the spring of 1845 (Felix announced its completion in a letter of April 26), and published with a dedication to the violinist and composer Ludwig Spohr. It has never been performed as frequently as the earlier work, but it certainly does not deserve this neglect.

Mendelssohn had been suffering from overwork for some time before this, mostly administrative red tape which interfered with his composing. So he spent the winter of 1844-45 in Frankfurt, his wife’s hometown, to allow some “decompression” and a return to composing, one of the results being this powerful trio, which begins not with a lyrical song (like the earlier D-minor work) but rather with a taut instrumentally conceived motive that already hints at Brahms. It is a more powerful Mendelssohn than we customarily encounter. Indeed, John Horton, in his short volume on Mendelssohn’s chamber music, asserts that “Mendelssohn never wrote a stronger sonata-form movement.” The violin and cello frequently mirror one another, and in the coda, both instruments play the theme in a broader version, with longer note values, while the piano accompanies them with the original version.

The slow movement has the gentle sentiment of Mendelssohn’s “songs without words,” a delicate respite from the energy of the opening and the elfin wit of the scherzo. The scherzo has a good bit of “Hungarian-gypsy” character projected, surprisingly enough, with touches of fugato. The finale reaches a typically Mendelssohnian expressive climax with the introduction of a chorale like theme. Attempts have been made to identify an actual reference to the Lutheran chorale Gelobet seist du (“Be thou praised, Jesus Christ”), but it is really rather an independent theme constructed on similar lines. Mendelssohn brings it to an almost orchestral peroration before the end.

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Trio No. 2 in E minor, Opus 67

When Shostakovich composed his Second Piano Trio in late 1943 and 1944 (the First had been a youthful work written in 1923 which Shostakovich called Opus 8, though he never published it), he was turning from large-scale orchestral works—especially the two wartime symphonies, No. 7 (“Leningrad”) and No. 8. In September 1943, he played through the Eighth for his closest friend, the musicologist Ivan Sollertinsky, in Moscow. He was trying to get Sollertinsky established there as well, because the years of the war had enforced a separation that was difficult for both of them. By mid-December the plans were set for Sollertinsky’s move. In early February 1944, the musicologist had given a lecture to introduce the local premiere of Shostakovich’s Eighth in far-off Novosibirsk. Less than a week later, after complaining of heart pains, he died suddenly at 41.

Shostakovich was devastated. To Sollertinsky’s widow he wrote to say how impossible it was to express the depth of his grief. “Ivan Ivanovich was my very closest and dearest friend. I am indebted to him for all my growth. To live without him will be unbearably difficult.”

Shostakovich began work on the Trio before Sollertinsky’s death, which occurred just a few days before he completed the first movement. Periods of depression and ill health in the spring—partly, no doubt, in reaction to his friend’s death—kept him from composing at all. In April, he wrote that “it seems to me that I will never be able to compose another note again.” By the end of the academic year, though, when his responsibilities as teacher and head of the committee evaluating pianists at the conservatory were finished, he returned to the Trio while spending the summer with his family at an artists’ retreat in Ivanovo.

At last he was able to work quickly, finishing the second movement on August 4 and the last on August 13. Then he turned quickly to his Second String Quartet, completing it in just over a month. Both works were premiered in November, when the Trio was particularly warmly received. Sollertinsky’s sister felt that in the second movement—the first written after the dedicatee’s death—Shostakovich had captured her brother’s “temper, his polemics, his manner of speech, his habit of returning to one and the same thought, developing it” with remarkable accuracy. At the same time, the work as a whole cannot fail to evoke the wider world situation in 1944, and throughout all four movements the mood is essentially elegiac.

The work opens with an astonishing texture, probably unique in the trio literature: a slow fugato with the cello in a high register, the violin entering in the middle, and then the piano in the bass. Throughout the work Shostakovich takes great pains to prevent the piano from overpowering the strings. The bulk of the first movement is in sonata form. It is followed by a scherzo-like movement in F-sharp, where the two stringed instruments band together, as it were, against the onslaught of the piano. The third movement is a passacaglia in the dark key of B flat minor, based on a series of eight chords sounded in the piano at the outset. These repeating harmonies modulate from B-flat minor to B minor and back. Over them, the violin and cello sing their mournful song. At the final statement, the B becomes a dominant to the home key of E minor, leading directly into the finale.

The last movement is cast in a kind of sonata-rondo form, but what is most striking is its half-mocking tone with uneasy shades of meaning. This has sometimes been called the “Jewish” part of the trio—a daring choice on the composer’s part at a time when the regime was often noted for its anti-Semitism. That portion had to be repeated, by audience demand, at the opening performance, on November 14, 1944.

The first performance was for a long time the last; almost at once it was forbidden to perform the Trio. Even now, seventy years after its completion, the work evokes tragedy and sorrow through artistic means. Just before the recapitulation in the last movement, there is a hint of the opening fugato, and the final hushed coda combines the passacaglia chords in the piano with broken statements of the movement’s main theme in the violin and cello—and the rest is silence.

Sergei Rachmaninoff (1873-1943)

Trio élégiaque No. 1 in G minor

Rachmaninoff left two piano trios, both of them labeled “elegiac”—intended, presumably, as some kind of act of mourning. The full-scale second trio in D minor was published as Rachmaninoff’s Opus 9; it was intended as a specific elegy in memory of Tchaikovsky, whose sudden death at the age of 53 on November 6, 1893, had been a terrible blow to the young Rachmaninoff, because Tchaikovsky had not only praised his early work at the conservatory, but also asked if the newly-graduated composer “would mind” if Tchaikovsky placed his graduation piece—a short opera called Aleko—on the same bill as Tchaikovsky’s own last opera, Yolanta. What an honor for a young musician just starting on his career. So it was only natural that, after Tchaikovsky’s death, Rachmaninoff would commemorate him with a piano trio, just as Tchaikovsky himself had memorialized his old friend Nikolai Rubinstein with a similar work.

But even before he had a specific reason to write such a memorial work, Rachmaninoff composed a short work in the same expressive mood—possibly inspired by Tchaikovsky’s tribute to Rubinstein, and little realizing how soon there would be occasion to write an actual memorial trio. Rachmaninoff composed the G-minor trio in 1890-91. The manuscript is dated January 18-21, 1892, though this short span of three days probably only refers to a period of touching up and polishing the score before it was to go into rehearsal for an important performance at the end of the month—Rachmaninoff’s first public concert outside the conservatory where he was a student.

It is clear that Rachmaninoff intended the piano part for himself, and he tends to overbalance the two stringed instruments—faults of youthful inexperience and exuberance. Still the opening theme, presented in the piano over a rustling figure in the strings, moves to cello and then to violin (in a low register) to maintain the dark expression of the opening. When the violin sings the second theme, we are in the territory of sweet salon music, less impressively rich than the opening, but still carrying forward the songfulness that was always a mark of Rachmaninoff’s style. The single movement of the Trio has many changes of tempo and brings back the basic thematic materials in many guises, but always with the brilliant writing that Rachmaninoff learned early to provide for his own instrument, while the other parts are less superbly conceived for the instruments—a relative weakness that Rachmaninoff overcame with more experience.

The final tempo marking for the coda, Alla Marcia funebre (“In the style of a funeral march”) justifies the “elegiac” title, but it does not seem to refer to any actual funeral; rather it allows the young composer to learn his art by setting up an expressive situation as a challenge to his growing talents.

Maurice Ravel (1875-1937)

Trio in A minor

Ravel enjoyed spending the summer in his Basque homeland. He arrived at St. Jean-de-Luz in the summer of 1913, fresh from the scandalous world premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in Paris, at which he had been abused by an indignant upper crust lady in the audience when he requested that she stop shouting her disapproval of Stravinsky’s score. The Basque country must have seemed exceptionally peaceful after such a hullaballoo, and Ravel found it almost impossible to tear himself away. He devoted himself to the composition of a piano trio, his first new piece of pure chamber music since the string quartet of a decade earlier (though he had been contemplating the trio since 1908), and, after the briefest possible return to Paris in the winter, he finished the first movement by the end of March.

Completion of the new work was interrupted by Ravel’s fruitless attempt to compose a piano concerto based on Basque themes. Once he had gotten bogged down with the concerto, he seemed to have difficulty in returning to the trio and even told a friend that he was getting disgusted with the piece. The impetus to finish the work came when Germany declared war on France in August. Composition became the means by which Ravel sought oblivion from the horrors that were inevitable.

Ravel had tried to offer his services to his country by joining the infantry but was rejected for being two kilos under the minimum weight. Always very sensitive about his small size, Ravel no doubt took the authorities’ assurance that he was serving France by writing music as a patronizing rejection, and he wrote to a friend, “So as not to think of all this, I am working—yes, working with the sureness and lucidity of a madman..” So it was that in just under four weeks, by August 29, 1914, he had completed the entire score of the trio. (Soon afterward, he was accepted into the air force, where he was put in charge of a convoy and composed virtually nothing else until his discharge in 1917.)

For all the haste with which it was finished, and despite Ravel’s distraught mind during the composition of the last part, the Trio remains a remarkable solid, well shaped work, one of the composer’s most serious large scale pieces (and it most assuredly is a large scale work, despite the fact that it is only for three instruments and not for an orchestra).

The opening Modéré presents a theme written in 8/8 time with the melody consistently disposed into a 3+2+3 pattern that Ravel identified as “Basque in color.” The second theme is a lyrical diatonic melody first presented in the violin and briefly imitated by the cello. These two themes and a tense connecting passage serve as the major ideas of the movement, building with increasing pace and intensity to a solid climax followed by a gradual descent to a gentle close.

The heading for the second movement, Pantoum, refers to a verse form borrowed by such French Romantic poets as Victor Hugo from Malayan poetry. What connection it has with Ravel’s music is a mystery. The movement serves, in any case, as the scherzo of the work, playing off a rhythmic string figure colored by the insertion of pizzicatos throughout and a simple legato theme that serves as the foil to the rhythmic motive.

As indicated by its heading, the Passacaille derives its shape from the Baroque form, more frequently labeled by its Italian name passacaglia, in which an ostinato melody or harmonic progression is repeated over and over as the skeleton background for a set of variations. Ravel’s approach to the form is, not surprisingly, a good deal freer than that of those Baroque composers who employed it, but the pattern is there to provide the framework for this wonderfully tranquil movement.

By contrast, the Animé of the finale offers gorgeous splashes of instrumental color in a masterly display of brilliant writing for each of the instruments—long trills in the strings serving as a foil for dense chords in the piano in a triumphant close.

© Steven Ledbetter (stevenledbetter.com)

Stay in touch with Celebrity Series of Boston and get the latest.

Email Updates Sign up for Email Updates